Stitching a Brighter World: Starting the Year with Pacita Abad

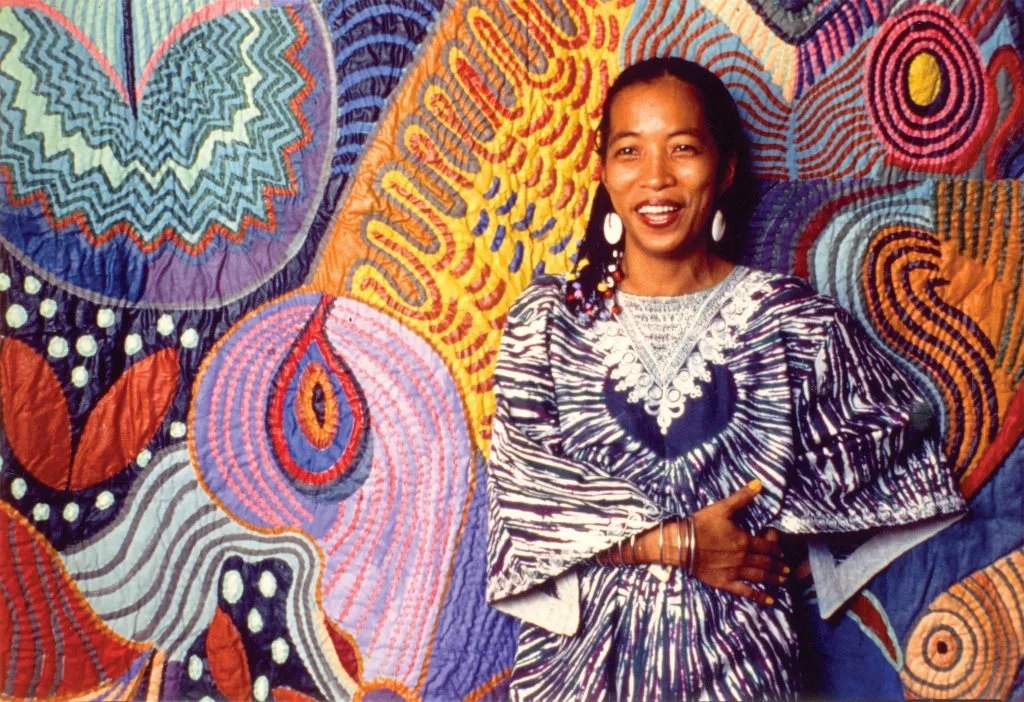

Pacita Abad with her trapunto painting Ati-Atihan, 1983. Photo courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate.

The new year has barely unfolded, and already the world feels heavy.

Most days begin with a scroll: headlines full of conflict, uncertainty, and a familiar mix of anger and exhaustion. It’s a strange dissonance - to be making coffee, feeding the pets, planning a work day, while the wider world seems to tilt and crack in all directions at once.

In this noise, I’ve found myself returning, again and again, to the life and work of Pacita Abad.

She’s been everywhere these past few years: major retrospectives, glowing reviews, museum banners in cities she never lived long enough to see her name on. But what stays with me isn’t just her belated fame. It’s the way she insisted on bringing colour, care, and political reality into the same frame, and how determined she was to keep stitching her own world together, even when the larger one felt hostile.

Starting this year with her feels right.

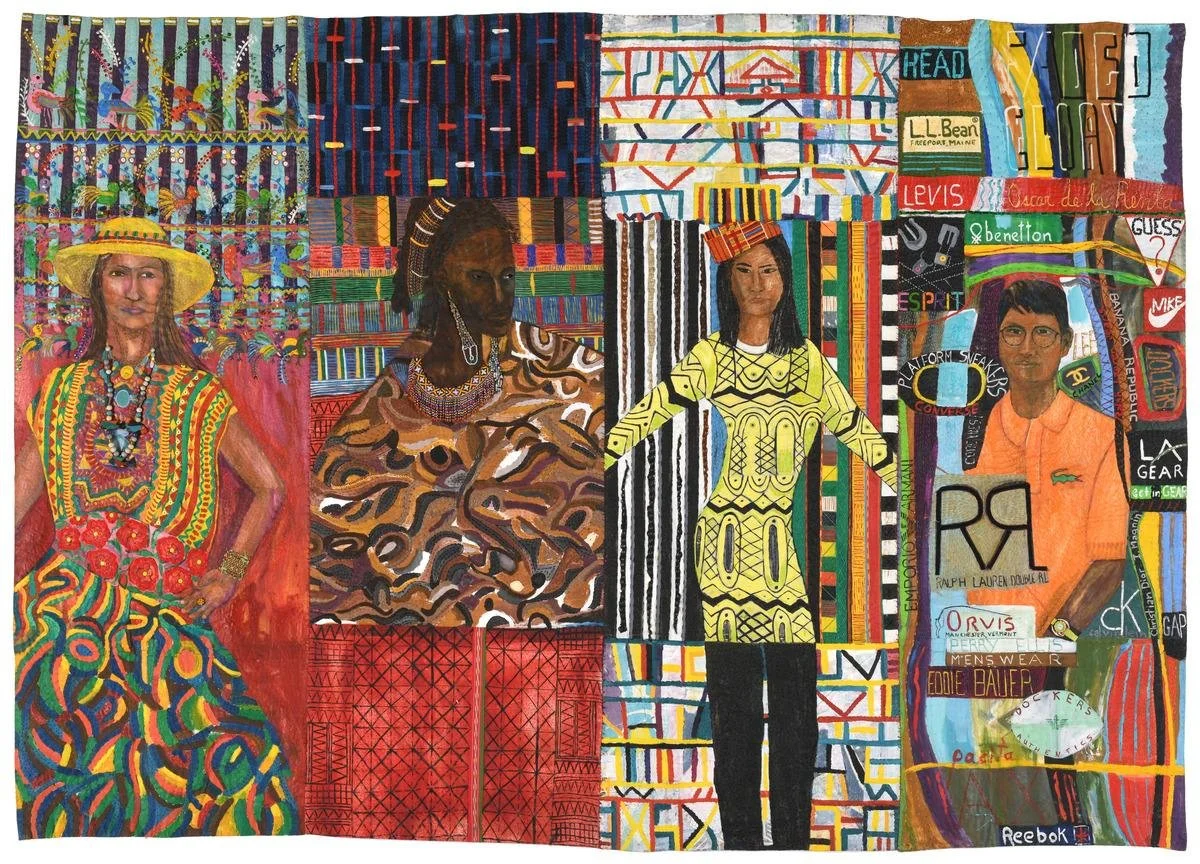

Pacita Abad. Cross-cultural Dressing (Julia, Amina, Maya and Sammy), 1993; Image Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate and Spike Island, Bristol

Pacita Abad was born in Batanes, at the very top of the Philippines, in 1946. She grew up in a politically active family and originally planned on becoming a lawyer. That path shattered in the 1970s when she helped lead student demonstrations against the Marcos regime. It wasn’t a symbolic opposition; it had consequences. She was forced to flee, landing first in the United States, thinking it would be a stopover on the way to somewhere else.

Instead, it became the beginning of an entirely different life.

In San Francisco, she started painting. That sentence sounds almost too neat, but it marks a massive turning: from law to art, from one country to a life that would eventually span more than sixty. She travelled relentlessly - Bangladesh, Sudan, Yemen, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Kenya, Singapore - absorbing what she saw in markets, textiles, street parades, boats, food stalls, crowds. She listened to people whose lives were rarely considered “central” and stitched what she learned back into her work.

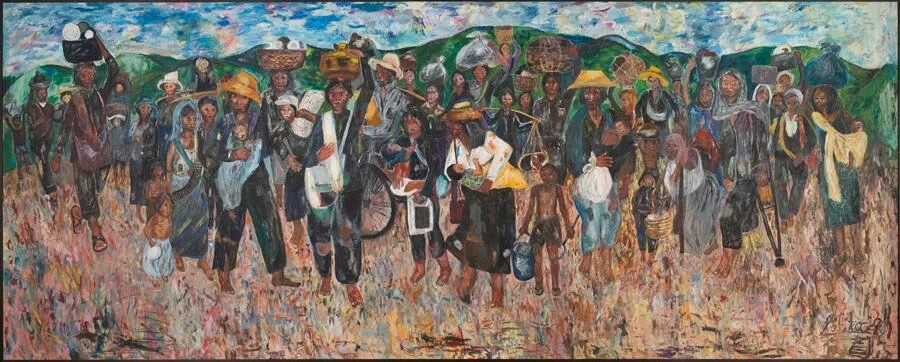

What I love is that she didn’t soften those stories to make them palatable. She painted refugees, undocumented workers, domestic labourers, mixed-status couples, shopkeepers, the people who held up a society quietly. She once said that artists have a responsibility to remind society of its obligations, and you can feel that belief in almost everything she made. Her work isn’t protest in a placard sense; it’s protest as an act of seeing fully.

Pacita Abad, Flight to Freedom, 1980, acrylic, oil on canvas. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and National Gallery Singapore

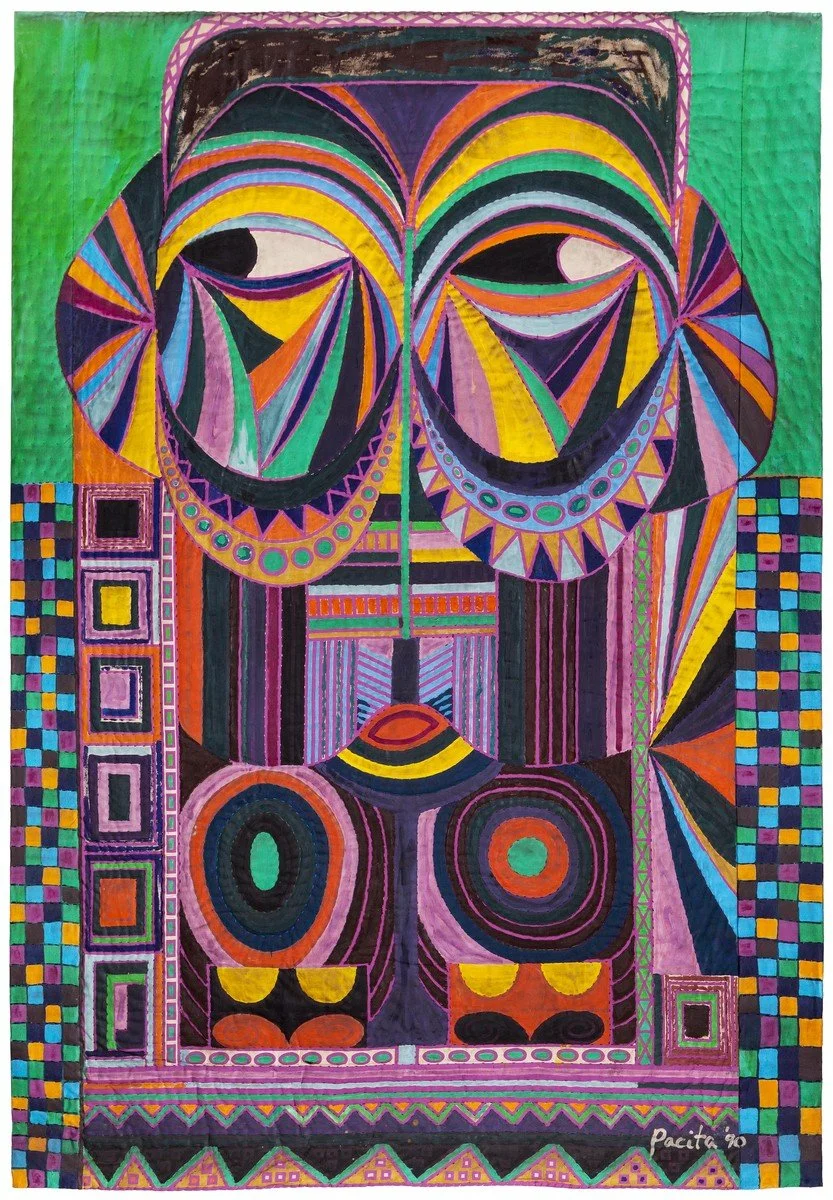

Pacita is best known for her trapuntos - large, padded, quilt-like works that hang like banners but behave like paintings. She stitched and stuffed her surfaces, then layered them with fabric, buttons, mirrors, lace, sequins, shells, whatever she could find. They look jubilant from afar: blazing oranges and pinks, saturated blues, dense patterns and ornament. Step closer and the stories sharpen.

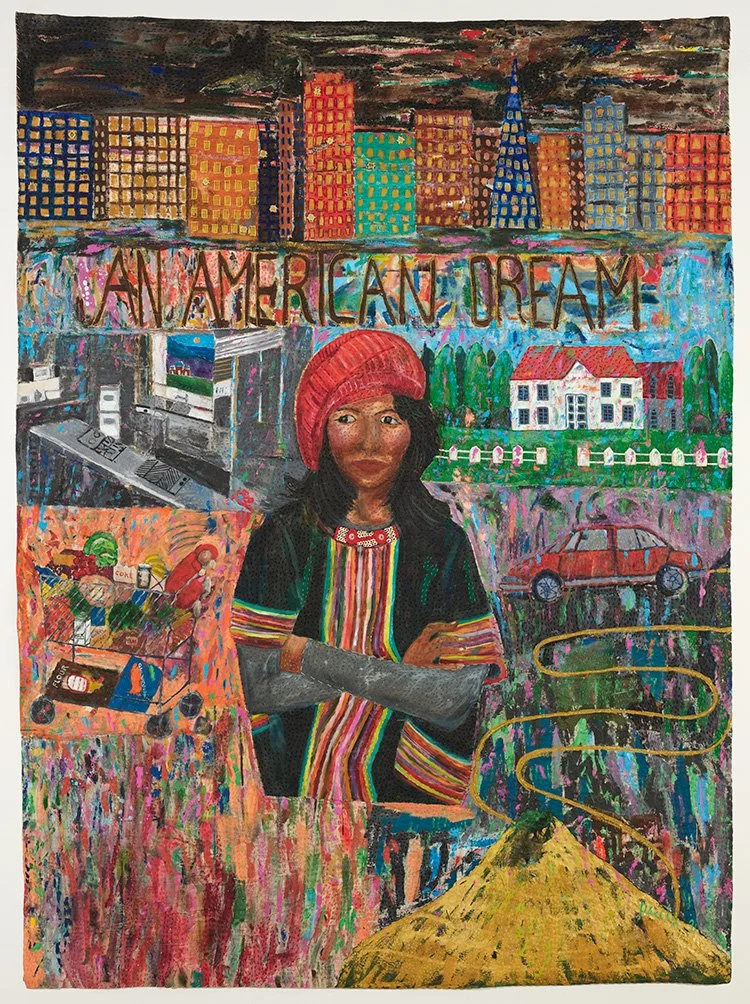

In the early 199s, she created her Immigrant Experience series while living in the U.S. The titles sound almost like fragments of overheard conversations: Caught at the Border, L.A. Liberty, Korean Shopkeepers, How Mali Lost Her Accent. The trapuntos themselves are crowded with figures, text, patterns, symbols of passports, planes, fences, city grids. They are not polite. They’re funny, angry, tender, and unapologetically busy, like the lives they depict.

Sometimes, when the news is full of headlines about borders, boats, visas, and detention, I think of those works. They were made decades ago, but they could have been made yesterday. They are a reminder that history doesn’t actually move in straight lines. The same fears and pressures keep resurfacing, and artists like Pacita keep insisting on human faces in the middle of them.

What strikes me most is how she refused to choose between joy and seriousness. The colours are ecstatic. The surfaces are almost baroque with texture. Yet the subject matter sits squarely in the realities of displacement, racism, labour, exile. She’s not using beauty as escape; she’s using it as a way to hold hard truths long enough to really look at them.

Pacita Abad, If My Friends Could See Me Now, 1991; Image Courtesy of San Francisco MOMA

When I think about Pacita right now, at the beginning of a year that already feels difficult, I don’t feel comforted in a soft, escapist way. I feel steadied.

There is something profoundly hopeful in how she moved through the world. Forced out of her home, she did not collapse inward. She kept looking outward. She learned from communities far from any “centre” of the art world. She treated everyday materials with respect. She made room in her work for people who were not often invited into galleries, and she did it in a visual language that refused to be shy.

There’s a lesson in that for how we live with art—and how we collect it.

Collecting with intention doesn’t have to mean buying work by artists with big museum careers. Most of us will never own a Pacita Abad trapunto. But we can let her story change the questions we ask when we stand in front of any artwork, at any scale.

Instead of “Will this go up in value?”, we might ask:

What kind of world is this artist stitching together?

Whose stories are held in this work?

Is this an image I want to live with, and in conversation with, day after day?

We can pay attention to artists who, like Pacita, work in the in-between: migrants, exiles, people who straddle languages and geographies, who make art while parenting, caregiving, surviving illness, navigating discrimination. We can honour “humble” materials—paper, fabric, found objects, small canvases—not as lesser, but as evidence of ingenuity and resourcefulness. We can allow ourselves to be changed by a painting or drawing or textile that speaks honestly about what it means to be alive now.

None of this needs to be grand. It could be as simple as choosing one piece this year that feels like a true companion rather than décor. Or deciding to learn the story behind a vintage work you’ve inherited. Or following an artist whose life experience is very different from your own, and letting their images quietly expand the edges of your world.

Pacita Abad, European Mask, 1990; Image Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate and Tate

There is always a risk, when writing about an artist like Pacita Abad, of turning her life into a neat metaphor: exile as resilience, hardship as fuel, vibrant colour as triumph. That would flatten her. Her story is more complicated than that, and she paid a real price for the life she lived. But the fact that her work exists, that it is still travelling, still meeting new eyes, still hanging in rooms where people stop and breathe differently in front of it, that feels like a kind of ongoing gift.

In a year that begins with so much uncertainty, I find it grounding to think about someone who made it her job to stitch pieces of the world together - places, people, fabrics, stories - and then offer those stitched worlds back to us as something we can stand before, inhabit, and learn from.

We don’t have to be Pacita Abad to adopt a little of that spirit.

Pacita Abad, Hundred Islands (1989); Image Courtesy of Tina Kim Gallery, New York.

We can choose to treat art not as background, but as a way of paying deeper attention.

We can let certain works become anchors in our homes when everything else feels in flux.

We can build small, intentional collections that reflect the values we want to hold onto, even when the wider currents are rough.

Jackie Bradshaw (Kitchener, ON)

Acrylic on Canvas Sheet and Fabric (Tapestry)

30” x 36” (Hanger not included)

The headlines will keep coming. The world will keep buzzing with things that are hard to bear. And still, there is this: a painting, a drawing, a quilted, hand-stitched surface glowing quietly on a wall, reminding us that making and looking and caring are still possible.

For this first piece of the year, that’s the note I want to carry forward: not denial, not naïve optimism, but a kind of stubborn, colourful hope - the kind Pacita Abad practiced with every stitch.