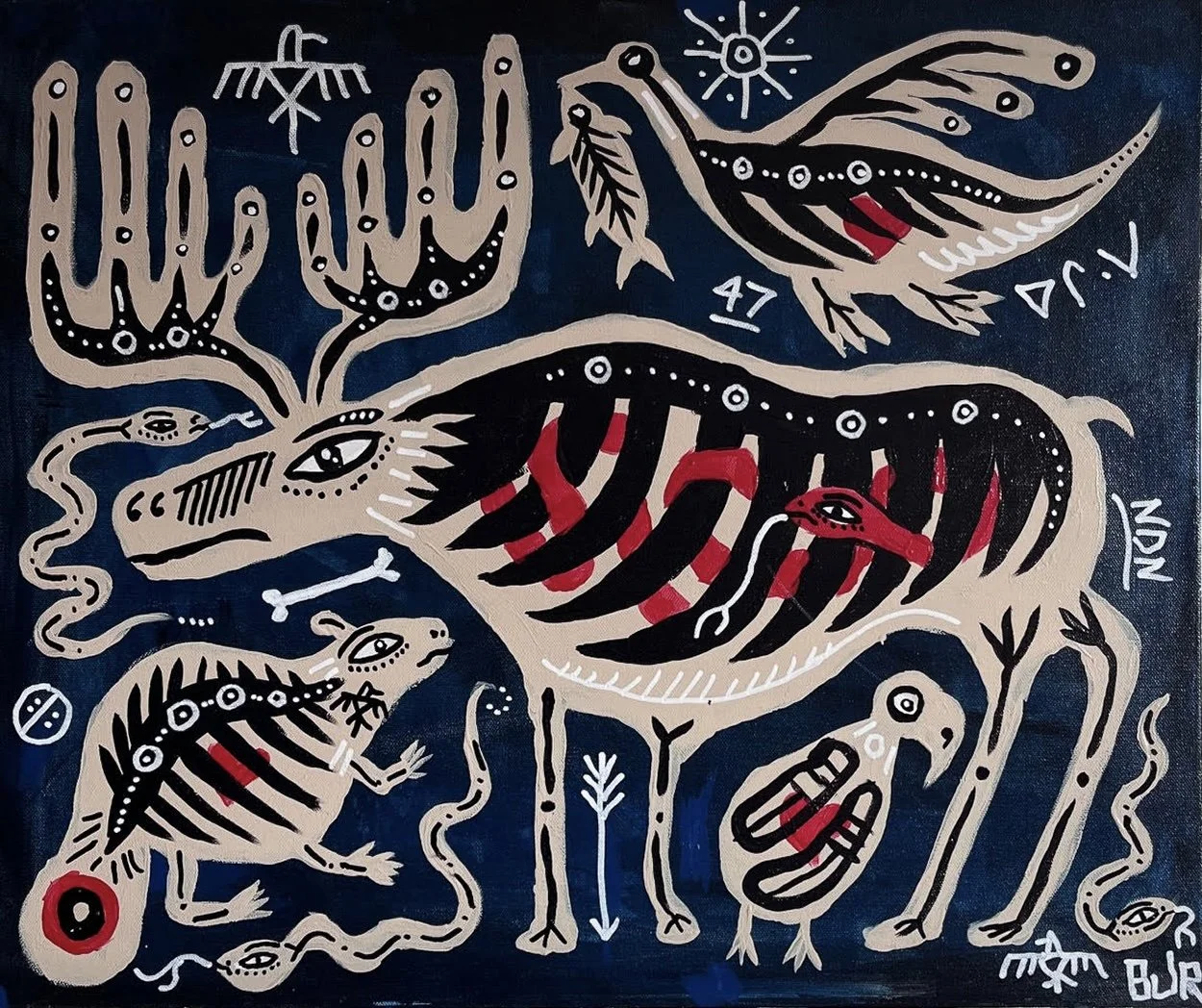

Artist Focus: Bradley Reinhardt

Thunderbirds, punk edges, and a new woodland language

Bradley Reinhardt (Toronto)

Acrylic on Canvas

20” x 24”

The first thing you notice about a Bradley Reinhardt painting is the snap.

The lines are crisp, the colours are unapologetically bold, and the forms sit somewhere between woodland tradition, pop graphic design, and a kind of low-key punk poster. It’s recognizably rooted in Ojibway visual language, but it’s not the woodland art you’ve seen a hundred times before. There’s a modern pop sensibility, a street-graphic sharpness, and a feeling that every shape has been carefully considered, then deliberately allowed to buzz with energy.

Bradley is an Indigenous artist from Batchewana First Nation of Ojibways in Northern Ontario, now based in Toronto. His work draws from the stories, symbols, and cosmology of his people, while also pulling in the visual worlds he grew up with: skate culture, punk rock, album covers, and the clean logic of graphic design.

The result is a visual language that feels both ancient and very now.

Woodland, but make it his own

Bradley Reinhardt (Toronto)

Acrylic on Canvas

24” x 24”

Woodland art comes with a strong, established visual grammar. As Bradley puts it, “it’s such a strong visual language on its own.” So what does it mean to paint inside that tradition without just repeating it?

“I give myself lots of permission to play in the style,” he told me. “My main goal when I started painting was that I wanted to do something my own… I hear the stories of my people and what comes out is my own interpretation.” The influence of Norval Morrisseau is there, clearly acknowledged, but not mimicked. Bradley’s paintings are dense with Ojibway iconography alongside other symbols from his past and present, all pulled together into compositions that feel distinctly his. “Ultimately,” he says, “it presents a piece of work that is entirely my own voice.”

That idea of voice matters deeply here. Bradley’s family on his mother’s side went through residential schools; a lot of language and culture that should have been passed down simply wasn’t. “My culture was lost instead of being passed down to me,” he says. “My art is a way for me to claw some of it back.”

Learning the language, naming the work

Many of Bradley’s titles use Anishinaabemowin. They’re short, strong words: Makwa (bear), Animkiig (thunderbirds), Mishipeshu (underwater panther). His grandparents spoke the language to each other, but he never got the chance to learn it properly before they passed. Now, he’s teaching himself, piecing together vocabulary through online tools and research.

“Many titles are just simply what the image is,” he explains. “But sometimes I’ll come across a phrase that I like and suits the painting. My paintings are spiritual, but I prefer people to feel something from looking at the image, rather than a title.” The titles, then, work like a quiet undercurrent: a way to thread language back into his daily practice, even as the paintings carry the emotional weight.

Lines, layers, and the graphic designer’s eye

Bradley Reinhardt (Toronto)

Acrylic on Canvas

16” x 12”

Part of what makes Bradley’s work pop so immediately is its graphic clarity. That’s no accident, he’s a graphic designer and art director by trade. “It’s important for me that pieces are well designed, balanced, graphic, and have a consistent colour palette,” he says. He often designs compositions on his iPad first, shifting elements around until the balance feels right. Symmetry, especially, has always appealed to him: many of his early works are almost mandala-like in their mirrored structures.

But underneath that crispness is a much looser, more experimental process than you might expect. Bradley frequently paints over finished works. “There may be 2 or 3 or even 4 paintings under it,” he says. “In my newer work, I allow some of the old paintings to peek through, so if you look close you can see it. If you hold my work up to a light source, you can often see other images.”

He’ll come up to the canvas, add something, take something away, move with intuition as much as design. “I do want people to feel the energy of the paintings,” he adds. “When I have shows, I enjoy people stopping, and being moved by the boldness of my work.”

As he grows, he’s also gently breaking his own design rules. It was hard, he admits, to push out of the comfort of his early, very symmetrical work. “As I grow as an artist, I am more and more just going at a canvas and letting my intuition and spirit guide me,” he says. “That might sound like BS but it’s the truth.”

Thunderbirds, bears, foxes, cardinals, panthers

Bradley Reinhardt (Toronto)

Acrylic on Canvas

20” x 24”

There’s a whole cast of recurring beings that travel through Bradley’s paintings. Some are cosmological, some are personal, all of them carry specific meaning.

“The thunderbird,” he says, “is a very important creature in Ojibway culture, and you will find it multiple times in every piece of art I do. I’m obsessed with it, I dream about it. I constantly reimagine the way it looks.”

Other figures are even closer:

The bear – his clan, representing himself and his family.

The fox – representing his love.

The cardinal – his mother and other loved ones who have passed into the spirit world.

Mishipeshu, the underwater panther – the darker forces in his life, often accompanied by snakes.

These aren’t just decorative motifs; they’re part of a living symbolic system. Over time, you start to recognize them in different configurations, like familiar characters dropping into new episodes of a long story.

Punk, skateboards, film sets, and reclaiming the image

There’s a strong “now” in Bradley’s work that sits right alongside its spiritual core. That comes from the visual cultures he grew up in: skateboard graphics, punk rock, bold album covers and posters.

“I grew up a skateboarder, and was really into punk rock,” he says. “All of that stuff comes from that. It’s a part of me I still gravitate towards.” Becoming a graphic designer was originally a way to design skateboards (he never ended up doing that professionally, but he has painted some boards). “I’m not afraid to add that stuff to my art. I paint for myself. I’m happy if people like it and want to hang it in their homes, but that’s not why I do it. I only started painting 3 years ago, so I leaned into what I know.”

In his current series, his day job in film and television has quietly slipped into the mix. Doing research for period sets (especially from the 1940s–70s), he noticed just how often Indigenous people appeared as flattened, stereotyped imagery in advertising and branding. “My most current stuff is looking at how Indigenous people have been portrayed in popular culture,” he explains. “I noticed a lot of Indigenous people being represented for advertising purposes, so I am taking that stuff and making it into my art.”

It’s a subtle but powerful shift: taking those old, colonial images and feeding them back through his own Ojibway visual language, on his terms.

Paintings as amulets

Bradley Reinhardt (Toronto)

Acrylic on Canvas

24” x 24”

When Bradley imagines his work out in the world, in someone’s home, the hope is clear.

He cites Norval Morrisseau, who said his paintings were like amulets, intended to provide protection and strength in the Anishinaabe tradition. “This is my goal and always has been,” Bradley says.

A viewer once told him his art reminded them of Mexican folk art – the colour palettes, skulls, mythical creatures created by Indigenous people. He took it as a compliment, another point of resonance across cultures.

The idea of protection feels apt here. These paintings may be bold and graphic, but they’re also shields of a kind: layered with personal symbols, stories, and beings that stand watch.

Bigger, bolder, and into the third dimension

Looking a few years ahead, Bradley is clear that he doesn’t want to limit himself.

“I will not limit myself, and continue to push to create new works. Bigger and bigger,” he says. “I’d love to do huge murals.”

He’s been experimenting with abstract expressionism, weaving his creatures into looser, more gestural grounds. He’s also curious about sculpture and other three-dimensional mediums: “to really bring my vision to life.” Whatever direction the work expands into, one thing is non-negotiable: “The Ojibway stories will always be a part of what I do,” he says. “It’s a part of who I am, and why I started painting.”

For Curio Atelier, that’s exactly what makes Bradley’s work so compelling: it carries the weight of those stories, but speaks them in a language that feels fiercely contemporary – part woodland, part punk show flyer, part amulet. These are paintings that don’t just sit quietly on the wall. They hold space, they protect, and they insist that old stories can be told in very new ways.